Your Quick Navigation

Let's cut straight to the chase. You're planning a trip, maybe to a mountain town like Breckenridge, Colorado (elevation 9,600 ft), or perhaps you're driving through the Sierras. You glance at your car's altimeter or look up your destination and see it's sitting around 4,000 feet. A thought pops into your head, a mix of curiosity and a tinge of worry: can you get altitude sickness at 4000 feet?

Most people associate altitude sickness with towering peaks like Everest or Denali. The brochures and travel blogs scream warnings about altitudes above 8,000 feet. So, 4,000 feet seems... safe, right? Almost trivial. It's not even a mile high. I used to think the same thing. I remember driving up to Lake Tahoe a few years back, feeling a dull headache coming on as we wound our way up the pass. I shrugged it off as dehydration or maybe just the stress of the drive. It wasn't until later, chatting with a park ranger, that the penny dropped. The connection was made.

The short, and perhaps surprising, answer is yes. You absolutely can experience symptoms of altitude sickness at 4000 feet. It's less common and typically less severe than at much higher elevations, but dismissing it entirely is a mistake that can ruin the first day or two of a well-planned vacation. This isn't meant to scare you off the mountains—far from it. The goal here is to arm you with knowledge, so you can recognize what's happening to your body and nip any potential problems in the bud.

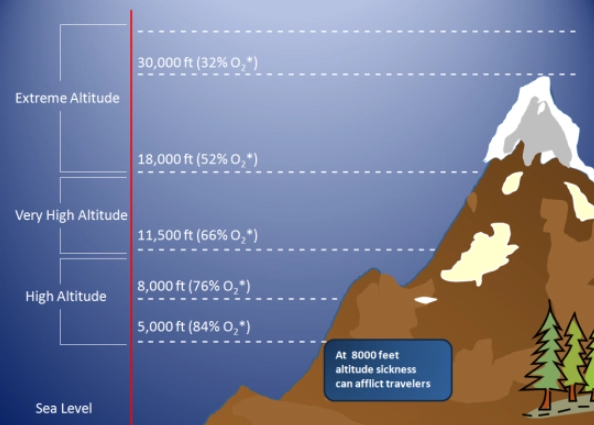

The Core Concept: Altitude sickness (also known as Acute Mountain Sickness or AMS) isn't about a specific altitude threshold you cross like a finish line. It's about the rate of ascent and your body's individual ability to adapt to lower oxygen pressure. Think of it as a spectrum of risk, not an on/off switch that flips at 8,000 feet.

Why 4000 Feet Can Be a Problem Zone

To understand why someone might ask "can I get altitude sickness at 4000 feet?", we need to ditch the idea that our bodies are perfectly calibrated machines. They're adaptable, but they need time. At sea level, the air pressure is about 760 mmHg. At 4,000 feet, it drops to roughly 630 mmHg. That's a significant drop—about 17% less pressure. While the percentage of oxygen in the air remains constant (around 21%), the lower pressure means there are fewer oxygen molecules in each lungful of air you take.

Your body notices this. It's a subtle shift, but for some people, it's enough to trigger the early alarm bells of altitude sickness. The people most at risk are those who live at or near sea level and then rapidly ascend to 4,000 feet or higher. If you fly from Miami (elevation 6 ft) to Reno, Nevada (elevation 4,500 ft) and then immediately drive up to a nearby ski resort, your body has had zero time to adjust. That's a classic recipe for feeling unwell, even if your final destination is the only place you've heard warnings about.

I have a friend, a perfectly fit marathon runner, who gets a pounding headache every single time he visits his family in Denver (the "Mile High City" at 5,280 ft). He laughs it off now, but his first visit was miserable because he just didn't expect it. He thought his fitness would protect him. It didn't.

The Individual Factor: Why Some Feel It and Others Don't

This is the million-dollar question. You and your partner can take the exact same trip. One of you feels great, ready to hike. The other is curled up on the hotel bed with a headache and nausea. It feels unfair, and frankly, it is. Science doesn't have a perfect answer, but several key factors are in play:

- Genetics: Some people simply have a genetic predisposition to be more or less efficient at acclimatizing. It's like a built-in setting.

- Rate of Ascent: This is the biggest controllable factor. Driving from Los Angeles (305 ft) to Big Bear Lake (6,752 ft) in two hours is a much bigger shock to your system than taking two days to reach the same altitude with an overnight stop.

- Previous Altitude Experience: If you've recently been at a higher altitude, your body might have some "memory" of the process (though this effect fades within weeks).

- Overall Health & Hydration: Being dehydrated, hungover, exhausted, or fighting off a cold or respiratory infection significantly increases your susceptibility. It gives your body one more thing to struggle with.

- Level of Exertion: Going for a strenuous hike or ski run immediately upon arrival is a surefire way to bring on symptoms. Your muscles demand more oxygen, exacerbating the shortage.

Recognizing the Symptoms at Moderate Altitude

The symptoms at 4,000 feet are usually the milder forms of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). They're often mistaken for other things—dehydration, travel fatigue, a mild flu, or even a hangover. That's why knowing what to look for is half the battle. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides excellent guidelines on this. The main symptoms often feel frustratingly ordinary:

- Headache: This is the most common symptom. It's often described as a dull, throbbing ache, typically worse in the morning or after physical activity.

- Fatigue or Unusual Weakness: You feel wiped out for no good reason. Walking up a flight of stairs feels like a marathon.

- Dizziness or Light-headedness: A feeling of being unsteady on your feet, especially when you first stand up.

- Nausea or Loss of Appetite: Food just doesn't seem appealing. You might feel queasy.

- Difficulty Sleeping (Insomnia): You're tired, but you just can't fall asleep or you wake up frequently throughout the night. This is a classic, under-reported sign.

When to Take It Seriously: If you experience symptoms like confusion, loss of coordination (ataxia), severe shortness of breath at rest, or a cough producing frothy sputum, these are signs of High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) or High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). These are severe, life-threatening conditions. However, it is exceedingly rare for these to develop solely at 4,000 feet. They are a major concern at much higher altitudes. The point is to know that AMS can progress, so don't ignore worsening symptoms just because you're "only" at a moderate elevation.

Here’s a simple way to think about it. If you have a headache and feel tired, it's probably mild AMS. If you have a headache, feel terrible, and also can't walk a straight line heel-to-toe, it's time to descend and seek help.

Mild AMS vs. Other Common Issues (A Quick Comparison)

| Symptom | Likely Altitude Sickness (at 4000 ft) | Likely Dehydration/Travel Fatigue |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | Dull, throbbing, often worse in AM or with exertion. May improve with oxygen or descent. | Can be similar, but often improves dramatically with drinking water and electrolytes. |

| Fatigue | Profound, disproportionate to activity. Rest doesn't fully resolve it. | Improves significantly with proper rest, food, and hydration. |

| Nausea | Often present without other GI issues. Food is unappealing. | May be accompanied by dizziness from low blood sugar or blood pressure. |

| Sleep | Frequent waking, restless sleep, feeling unrefreshed. | May sleep very deeply due to exhaustion. |

| Key Test | Does it get better if you go down 1,000-1,500 feet for a few hours? | Does it get better after drinking 0.5-1 liter of water and resting? |

Smart Strategies: How to Prevent Feeling Terrible at 4000 Feet

The good news is that since the risk is lower at this altitude, prevention is usually straightforward and highly effective. You don't need prescription drugs like Acetazolamide (Diamox) for a trip to 4,000 feet, unless you have a known severe susceptibility. The basics are your best friends.

- Hydrate Like It's Your Job: This is rule number one, two, and three. Start increasing your water intake 1-2 days before you travel. On travel day and for your first 48 hours at altitude, drink enough water so that your urine is consistently pale yellow. Avoid excessive alcohol and caffeine initially, as they are diuretics and can worsen dehydration.

- Slow Your Ascent If Possible: This is the golden rule of altitude. If you can, plan your trip so you don't go from sea level to 4,000+ feet in a few hours. Can you spend a night at 2,000 feet on the way? Even a few extra hours can help. If flying directly, take it very easy on your first day.

- Listen to Your Body (Really Listen): That planned 5-mile hike on arrival day? Postpone it. Your first day should be for gentle activities—walking around town, light sightseeing. Let your body use its energy for acclimatization, not for powering your quads.

- Eat Light, Carbohydrate-Rich Meals: Your body metabolizes carbs more easily at altitude, requiring less oxygen than it does to process fats and proteins. Go for pasta, bread, fruits. Avoid huge, heavy, greasy meals.

- Consider a Pulse Oximeter: This is a little gadget that clips on your finger and measures your blood oxygen saturation (SpO2). At sea level, a normal reading is 95-100%. At 4,000 feet, it might drop to 90-95%. It's not a diagnostic tool for AMS, but if you see your SpO2 is unusually low for the altitude (e.g., 85%) and you feel bad, it's a clear sign your body is struggling.

My own rule of thumb? I never plan anything strenuous for the first 24 hours after a significant altitude gain. I drink water obsessively, I eat bland carbs, and I go to bed early. It's boring, but it guarantees I'll enjoy the rest of my trip. It's a trade-off I'm always willing to make.

What to Do If You Feel Sick at 4000 Feet

Okay, you've read all this, but you're already there and you've got that nagging headache and a stomach that's doing flips. Don't panic. The treatment for mild AMS at this altitude is simple and effective.

- Stop and Rest: Seriously, just stop. Cancel your plans for the afternoon. Lie down, read a book, watch a movie. Do nothing strenuous.

- Drink Fluids: Sip water or an electrolyte-replacement drink consistently.

- Consider Pain Relief: Over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen can help with the headache. I find ibuprofen works better for me, as it also helps with inflammation.

- The Descent "Test": If you can, drive or walk down to a lower elevation, even just 1,000-1,500 feet lower, for a few hours. If your symptoms improve noticeably, you've confirmed it's altitude-related. Often, just knowing what it is provides mental relief.

- Do NOT Ascend Further: This is critical. If you're feeling unwell at your lodge at 4,000 feet, going up to that 6,000-foot viewpoint will almost certainly make things worse. Wait until you feel completely better for at least 24 hours.

Most cases of mild AMS at this elevation will resolve completely within 24-48 hours if you follow these steps. Your body just needs that time to catch up.

Clearing Up Common Myths and Questions

Frequently Asked Questions

The Bottom Line: Respect the Altitude, Enjoy the Trip

So, we've circled back to our core question. Can you get altitude sickness at 4000 feet? The evidence is clear. It is a real possibility for a meaningful portion of the population, particularly those making a rapid transition from near sea level. It's not about being weak or unhealthy; it's about physiology.

The key takeaway isn't fear. It's empowerment. Knowing that it can happen allows you to prepare. Understanding the simple, non-pharmaceutical prevention strategies (hydrate, ascend slowly, rest) gives you control. Recognizing the symptoms means you won't waste a day wondering if you're getting the flu, and you'll know exactly how to treat it.

Don't let the worry overshadow the beauty of being in the mountains. The crisp air, the stunning views, the sense of space—it's all worth it. A little bit of knowledge and a conservative plan for your first day are a small price to pay for a fantastic, symptom-free adventure. Pack your water bottle, plan a lazy first afternoon, and then go enjoy that 4,000-foot vista in full health.

Remember, the mountains aren't your enemy. A lack of preparation is. Now you're prepared.

Comments

Join the discussion